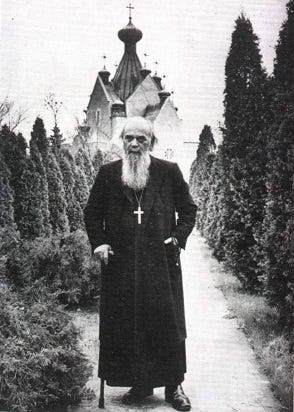

I recently began reading through The Universe as Symbols and Signs by St. Nikolai Velimirovich as part of our project to systematically collect, categorize, and comment on all of the writings of the Church fathers, all the way from the earliest apostolic fathers to modern saints such as Fr. Dumitru Staniloae and St. Nikolai himself. The book is, essentially, an Orthodox version of James B. Jordan’s Through New Eyes, as both men–despite their theological differences–take a “nitty-gritty” approach to the question of Biblical symbolism and typology. Instead of engaging in abstract theological speculations, they focus on the concrete realities of God’s creation, demonstrating how the Bible teaches that every creature uniquely expresses something of the life of God.

While Saint Nikolai and Jordan focus on the “empirical” examples of the Bible’s symbolic language, their insights are only meaningful within their overall worldview–the symbolic worldview. Yet, this symbolic world can equally be described as a “communal world.” That’s because our communal ontology is identical to Jonathan’s “symbolic world,” as both are two modes (with their unique idioms and patterns of emphasis) of describing the same reality created by the same God.

To say that the world is “symbolic” is to make a profoundly ontological claim that is best understood by the doctrine of creation ex nihilo. Creation ex nihilo guarantees a symbolic world, as it means that, from the outset, the “truth” of everything is not found “in itself” but in the “real” that it symbolizes. Thus, there is a “hierarchy” of truth itself, with the Truth being the Creator who freely brings forth creatures to exist in, through, and for Him. However, the doctrine of creation ex nihilo (or, at least, as it's understood in Christianity–but I think the following is intrinsic to the logic of creation) implies a novel understanding of “hierarchy” as well. Because all creation is a gift of the Creator, the reason He is at the top of the hierarchy is that He is the most generous of all. He is Generosity as such. In our fallen world, we typically understand hierarchies more-or-less in terms of domination and exploitation (especially in modern times). The person at the top is understood to have fiercely competed for their position, and their power comes at the expense of another. But the Cross completely reverses the logic of the world. On the Cross, the glory of the impassible, almighty and omnipresent God is identical to His “shame” because the “glory” (divine energies) of God is precisely His communal/kenotic (Trinitarian) life that is fully manifested in Christ’s willingness to self-empty on the Cross for the sake of the world. The essence of the Cross and of creation are, therefore, one and the same: self-sacrificial love.

St. Nikolai describes the “hierarchy of truth” as follows: “When we talk of visible things, of their properties and their mutual relations, and when we say: this and that is truth, we do not think of the truth in an absolute and eternal sense, but in a relative and practical sense, for in an absolute sense God alone is eternal Truth.”1 Only God is truly real because God has “life in Himself.” Everything else is only true derivatively, or, to put it in more positive (and perhaps accurate) terms–by participation. And this is what it means for us to live in a truly “symbolic world.” A symbol is an image of the real, a reflection or an expression of Being, but this “reflection” is, by necessity, equally an ontological participation (as God is Being as such).

This does not mean the world is “half true” and God “fully true,” as if Truth were subject to the logic of quantity. Rather, our “truth” is different “in kind” from God’s, and yet, this difference of kind/nature can only be conceived in terms of God’s creation of the world in His likeness. As such, the “difference” between God and creation does not negate the possibility of reaching the perfection of communion, but it is the proof of God’s generosity–the very condition of our union with Him. In deification, God’s mode of being truly becomes ours (by participation/grace), which occurs through our communion with Him. But this communion does not consist of God monergistically “taking over” our individual wills. It is a synergy wherein our distinct wills are preserved but brought to rest through attaining their end. But, as Maximus the Confessor says, this “rest” has the paradoxical character of being equally “ever-moving.” The key point of this antinomy is not that “rest” and “ever-moving” exist in some dialectical relationship but that our “resting” in God is precisely the completion of what we already are from the beginning–participation in the infinite God. Rest is thus found in movement and movement in rest, and that is because the life of God is one of “active communion” that is so perfectly realized it knows no shadow of turning.

The same logic applies to our “likeness” to and “difference/distinction” from God. As our unique, infinite potential for communion with God is actualized, the horizons of our personal existence expand into infinity. Hence, our distinctions from God increase and become more crystallized in proportion to attaining His likeness. Hans Urs von Balthasar understands this logic as “the more,” where the increase of an opposite correlates with a simultaneous increase in the thing itself. This is not only the logic of creation but the logic of God Himself. David L. Schindler explains it concisely:

We begin with an affirmation that casts an illuminating light on everything that is to follow. Balthasar, following Adrienne von Speyr, sees as characteristic of the trinity the relation of "the more" (Je-mehr): "The more the persons differentiate themselves in God, the greater is their unity." Unity and difference within the trinity, in other words, are not inversely but directly related: the one is not exclusive of, but is the condition for and indeed the meaning of, the other. Unity and difference (dynamically) deepen each other, rather than remain either (statically) juxtaposed to or (dynamically) sublating of each other. Such a relation of unity and difference is therefore best understood in terms of paradox, rather than either mere indifference on the one hand or dialectical opposition on the other.2

I can’t think of a good conclusion, so make sure to follow

and consider supporting us for access to our full archive of posts!Nikolai Velimirovich, The Universe as Symbols and Signs

https://www.communio-icr.com/files/1991_Spring_Schindler.pdf

As you rightly point out, the belief in creation ex nihilo not only “guarantees” but necessarily requires creation to be understood as symbolic - that is, as you said, “different in kind/nature” from God. These are dualistic beliefs rooted in ontological separation between God and creation.

Alternatively, I argue and humbly ask you to consider the possibility that creation is not created ex nihilo or symbolic, but is in fact ex Dues and truly sacramental. Creation isn’t an ontologically disjointed sign that points to the Truth, but is the very manifestation of Truth itself - God incarnate as creation. Creation is not different in kind/nature from God. Sacramental creation is the very revelation and presence of God as creation.

This is exactly what Jesus Christ revealed and is the very purpose of the Incarnation. The Incarnation did not ontologically unite or re-unite the symbolic with the real and true. The Incarnation reveals the sacramental nature of creation. As the man Jesus, Christ didn’t become something other than God, become a symbol of God, or unite ontologically separated divine and human natures.

Likewise, through deification, man does not become united to the God who is separate from him, but rather actualizes the inherent and essential divine potential which he (and all of sacramental creation) truly is. Likewise, the bread and wine of the Eucharist, as sacrament, do not become something that they aren’t, but are revealed as that which they always already are - God’s presence and inherent communion with, in, and as creation.

Wonderful work here! When I first read AllHeart's article on Christian phenomenology I realized that the modern obsession with a "literal" description of reality and the degradation of the value of symbolism to a function of mere adornment coalesces perfectly with the self-relational logic of the modern conceptions of knowledge, freedom and relationships. A "pure literal meaning" is a vacuous notion, it is A = A, tautalogical indeterminacy, absolute self-relation. There isn't a "literal" dimension of reality and a "symbolic" dimension superimposed onto it, all of reality is always-already symbolic, being is communion means being is symbolism.