If Being is Communion, Evil is Self-Relation

Sin as Rebellion Against the Ontology of Creation

If creation (including human reason/thought) is equal to precisely zero in the absence of its constitutive and essential relation to God, both to “be” and to “know” anything is to participate in God. To be is to participate within (or be) God. Therefore, the “good” of all beings is the continuation and, if possible, deepening of this communion. The ultimate folly, the irrational “reason” of evil, is a creature’s attempt to be (or know, grow, etc.) excluded from participation in God. There is no “reason” for such futile, self-negating/impossible intentions of creatures. More precisely, no “reason” can be separated from the “evil desire of the heart” of the creature to provide some intelligible articulation of its cause/essence/purpose. This is not an “epistemological” obstacle; on the contrary, evil cannot be explained because it is, in itself, unintelligible and an ontological impossibility. It is unintelligible because it is self-referential.

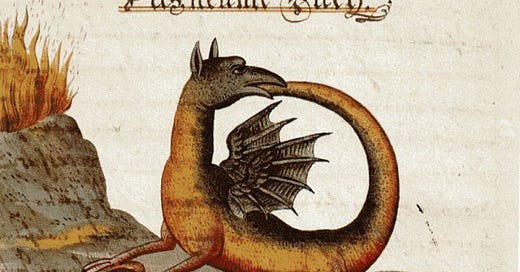

Since it is self-referential, it does not truly exist, as being is communion. Evil “as such” is, in truth, an ontological impossibility, as to say evil “as such” can only mean the actual realization of complete self-referentiality (this is the evil desire of every heart, which we can already see implies warfare, as there are multiple hearts with self-referential desires). This, we may say, is imaged in the ouroboros, the Serpent eating its own tail. But as G.K. Chesterton humorously notes, one’s tail is “quite an unsatisfactory meal.”1 Chesterton’s insight here is crucial: the ouroboros is not an image of complete, totalized, and eternalized self-referentiality (equivalent to popular conceptions of Hegel’s “Absolute Knowing”), but rather the pitiful, self-negating and ultimately impossible image of an identity whose mode of being (itself) is solely self-referential. The Serpent was not born with its mouth on its tail; it chose to do so. In selecting its tail instead of consuming real food, it withdrew from the environment necessary to sustain its existence. This withdrawal is not neutral with respect to one’s own state because any creature can only “withdraw” into a “space” that it itself has access to; if withdrawal literally is the withdrawal from any external “space,” it can only ever, ultimately, be withdrawal-into-self (which negates the very conditions of true selfhood realized in relation to other selves). The self-consumption of the ouroboros is, quite evidently, a self-negating movement, one that concludes with a gaping mouth that has consumed all of its “body” and remains as a mere void of desire, an empty intention (for an impossibility, which has been fully actualized/revealed as impossible through utter self-negation).

It is an ontological fact that an activity can either be participation in God or withdrawal into the self (of course, until the Last Day, these two–wheat and chaff–are not absolutely distinguished). An activity can be referred to as an act of “withdrawal into self,” but it can only be so partially, temporally, and to the extent that it is withdrawal into self it is not an activity in the true sense. Withdrawal-into-self, that is, activity motivated by self-interest (the undefinable “evil desire of the heart,” pride), is self-negating in the most fundamental sense, which is that the activity of withdrawal/destroying relations is the negation of the very possibility of fulfilling the true desire of one’s heart. It is an activity that, ultimately, destroys the possibility of action, which can only be realized through communion with God. Evil activity, therefore, can only be a parasitical reality that involves the temporary and partial realization of a self-referential desire through the (mis)use of being that is not created, explained, sustained, or properly governed by this desire. Therefore, it is “ontologically unlawful” for a creature to sin, as it is a rebellion of the heart (which manifests outwardly in action) that cuts against the ontological constitution of reality as ordered relations of mutual interiority. The end of this activity is the full “emptying” of the evil heart/soul from all relations to others, although one that cannot be totally completed (which would be, by ontological necessity, the equivalent of annihilation). The “end” of total self-relation (once again, an impossible ideal) is the lie that motivates the sin. The true end is, rather, the total realization of the contradiction of pride, which comes to be revealed as impotent, meaningless, and the cause and essence of sin. This is Gehenna.

This is part of the introduction to my and Nate’s upcoming book, Anagogia: Modern Philosophy Through New Eyes.

G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy.

Thank you for writing this. It’s an interesting perspective. 🤔

And look came up in my YT feed: https://youtu.be/wxg468NL3S8?si=zuyz6doAS74YTGG_

Pageau discussing Ouroboros. 🤔