I

Rest me with Chinese colours,

For I think the glass is evil.

II

The wind moves above the wheat-

With a silver crashing,

A thin war of metal.

I have known the golden disc,

I have seen it melting above me.

I have known the stone-bright place,

The hall of clear colours.

III

O glass subtly evil, O confusion of colours!

O light bound and bent in, soul of the captive,

Why am I warned? Why am I sent away?

Why is your glitter full of curious mistrust?

O glass subtle and cunning, O powdery gold!

O filaments of amber, two-faced iridescence!1

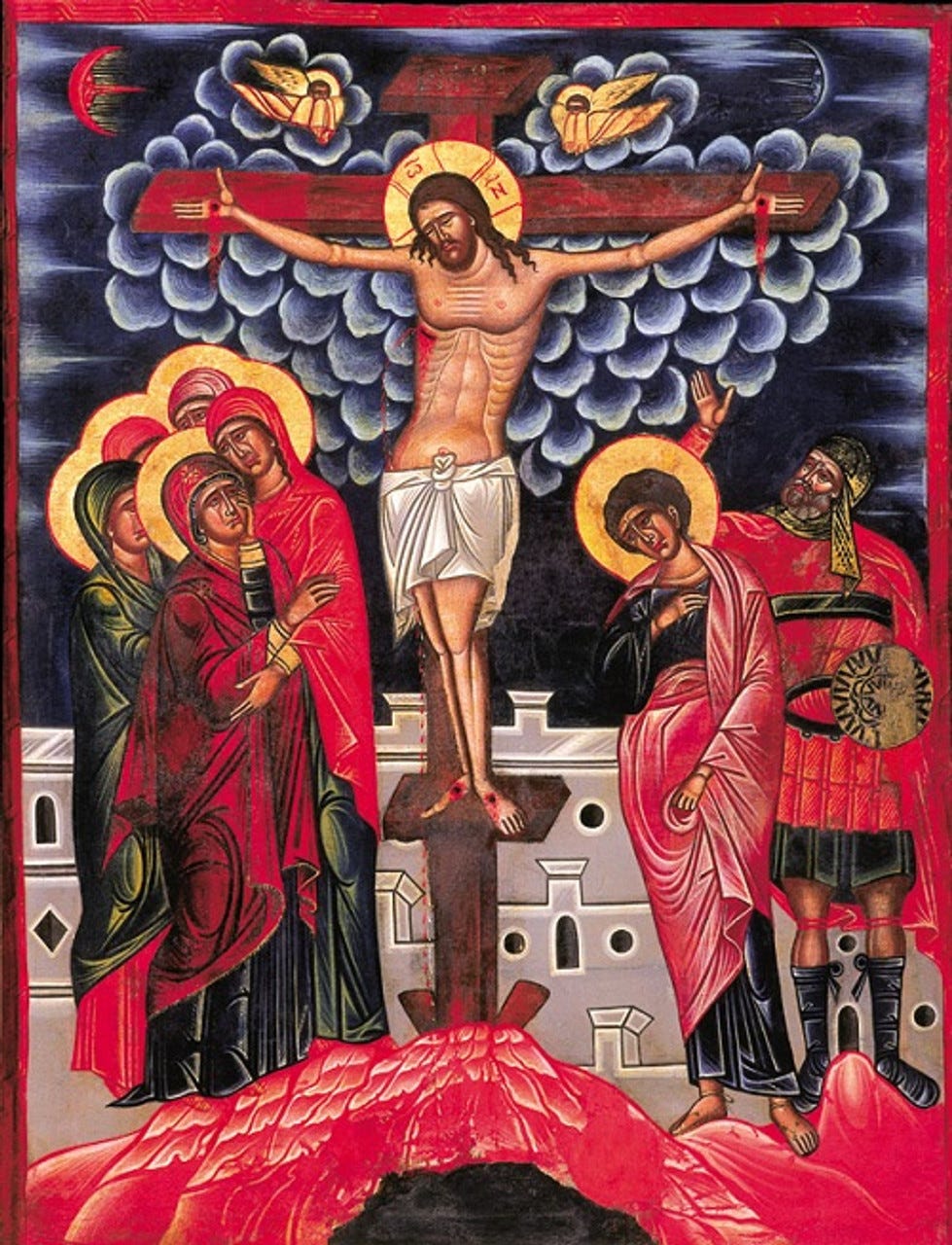

“And about the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” that is, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”2

“Why am I warned? Why am I sent away?”

Spiritual ruts are often accompanied by a cruel feeling of chastisement or abandonment on behalf of the divine. If you have experienced this–or are currently one with this reality–and you believe that God has a personal vendetta against you: fret not. This experience of feeling abandoned is not unique to any of us; David experienced it, after all3. Not only is this experience not unique to any one of us, it is actually one of the most primordial human memories–one of the most prevalent ingredients in the glue of collective experience, by which humanity is bound.

“Then the Lord God said, “Behold, the man has become like one of us in knowing good and evil. Now, lest he reach out his hand and take also of the tree of life and eat, and live forever—” therefore the Lord God sent him out from the garden of Eden to work the ground from which he was taken. He drove out the man, and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim and a flaming sword that turned every way to guard the way to the tree of life.”4

Why, upon eating of the tree of knowledge of good and evil were Adam and Eve cast out from the paradisiacal garden of Eden? Why would God condemn Adam and Eve to a life of pain, death and wandering in the wilderness–barring the two from the tree of life? Would not the fruit of the life-giving tree reintroduce fallen man to their prior innocence? Why does the face of God veil itself when we need it most? This is the same question asked above by Ezra Pound and is the same question asked by many of us when we find ourselves bound by the bowels to despair in the sulphuric mud pots of graceless abandonment.

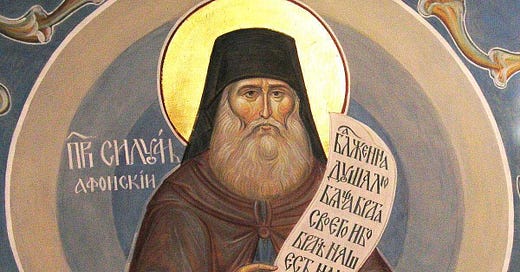

St. Silouan the Athonite (1866-1938), a familiar name for many of us, was granted, following shortly after his tonsure as a monk, a taste of Eden’s deathless fruits: prayer of the heart, visions of Christ, and more. This paradisiacal grace proved however to be less congruent with the symbol of an eternal garden and something more along the lines of a heavenly ephemeral, and fugacious bouquet which—as a collection of flowers wrought from their roots tends to—inevitably faded and withered. St. Silouan relished in the glory of the graced sun of God’s divine light for a time, but “the lotus can’t endure the cold”5 and all time—as the ancient preacher once explained6—must reveal itself in all its circumpolar chiaroscuro. With such haste as St. Silouan ascended atop the zenith of noonday, descended the obfuscation of dusk upon his zealous eyes. The numinous noon hour’s luminosity was followed by fifteen years of a suspended parabola of darkness from starless dusks to shadowy midnights which not even the silver moon could elucidate with her gentle gaze. This prolonged period of gracelessness is what inspired the rightfully famous quote: “keep your mind in hell, but do not despair”.

St. Silouan—as someone who lived what he preached—spends a significant portion in his “His Life is Mine” explaining the Christian life as the progressive embodiment of the Lord’s prayer in gethsemane by the soul till the heart dwells therein, immersed in its fragrance and nourished by the very dew which once watered that garden.

“Abba, Father, all things are possible for you. Remove this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will.”7

Christ, in the gospel of John informs us that no longer are we considered slaves, “for the servant does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends, for all that I have heard from my Father I have made known to you.”8 Similarly, St. Paul explains, in Galatians 4, that in Christ we are not considered slaves, but rather Christ was sent “so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’ So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God.”9 A consistent theme–perhaps the most deserving theme of the title ‘consistent’--in scripture is that of inheritance. From the cultural mandate given to Adam, to the covenantal selection of Abraham, to the salvation of humanity through the dwelling of God therein through Christ, the bible is very clear that the purpose for which we exist is to share in the inheritance–the glory and riches–of God. Romans 8 makes it very clear that what it means to be a Christian is to be united to the relationship which Christ has, as the trinitarian Son, to the Father in the Spirit, which entitles us as co heirs with Christ to His inheritance as Son. Romans 8 makes it equally as clear that the manner in which we become adopted heirs in, through and with Christ is in and through the Spirit’s crying of “Abba, Father!” in our hearts.10 This cry is the witness of the Spirit who pronounces us “heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him.”11

Galatians 4 and Romans 8 comprise the only two times other than the initial reference in Mark 14:36 that the bible uses the phrase “Abba, Father.” This means that what it means to be a Christian–what it means to be included in the divine inheritance–is, by the very nature of what it means to be a coheir with Christ, to be a participant in His prayer of gethsemane. To be a participant in Christ’s inheritance of the riches of the Father is also to be a participant in the cup of Christ–the cup which the Father poured for Him in that dread garden.

“Beauty is vapour from the pit of death”.12 To live in Christ–that is, to live at all–is to find the border of the pit of death and to rise beyond it in the vapour of beauty. Vapour only arises, however, when held above the flame. Hold water above a flame and eventually it will begin its evaporative ascent towards the heavens, but sometimes this boil takes longer than expected. A geyser erupts with sudden apocalyptic vehemence. What is hidden beneath the dramatic exhalation of molten life, however, is extended periods of underground boiling. Beneath the volcanic immediacy of the geyser’s explosive ascent is sometimes years of heating. While sometimes the Christian life seems ineffectual or ineffective, we must continue–a geyser would never erupt without the invisible excitation behind the scenes.

To live is to die, and sometimes this death is dramatic and transmundane; other times it is a dull, quotidian, lingering dissolution.

When they had finished breakfast, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Feed my lambs.” He said to him a second time, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Tend my sheep.” He said to him the third time, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” Peter was grieved because he said to him the third time, “Do you love me?” and he said to him, “Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.” Jesus said to him, “Feed my sheep. Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you used to dress yourself and walk wherever you wanted, but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will dress you and carry you where you do not want to go.” (This he said to show by what kind of death he was to glorify God.) And after saying this he said to him, “Follow me.”

Peter turned and saw the disciple whom Jesus loved following them, the one who also had leaned back against him during the supper and had said, “Lord, who is it that is going to betray you?” When Peter saw him, he said to Jesus, “Lord, what about this man?” Jesus said to him, “If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you? You follow me!” So the saying spread abroad among the brothers that this disciple was not to die; yet Jesus did not say to him that he was not to die, but, “If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you?”13

Regardless, let us bear our cross with dignity and follow the Christ who endured more than we can ever imagine. Let us burn with the passion of a suffering servant before our God, like candles upon the sacrificial altar. Candles, which only emanate their scent only in the self-sacrificial ecstasy of melting.

St. Silouan, pray for us, that we may join alongside you in Christ’s gethsemane prayer, and that no matter how mundane things become we will never fail to find the hidden flame upon which we can burn and deliquesce into the incense which rises constantly upon the Lord’s altar of love.

A Song of The Degrees, Ezra Pound

Mt. 27:46

Ps. 22 (and much more)

Gen. 3:22-24

The Cold Mountain, Han Shan

Ecl. 3

Mk. 14:36

Jn. 15:15

Gal. 4:5-7

Rom. 8:15

Rom. 8:17

The Peregrine, J.A. Baker

Jn. 21:15-23

This is beautiful, thank you.