In our conversation with D.C. Schindler, I asked him about the existentialist—specifically Sartrean—association of freedom with some primordial negativity, a violent rupture from or within Being, an ontological “hole” in place of the ontological “whole.” Dr. Schindler, quite refreshingly, asserts the radically “theological” claim that freedom, meaning, intelligibility, etc., is only even possible in light of some ultimate ontological “whole” that accounts for every particularity.

While not without its merits (and significance for its time), the postmodernist critique of “totality” ultimately misses the mark. One can affirm a genuine metaphysical monism on account of the Trinitarian and Christological language we’ve inherited, one that does not imply either political or metaphysical “totalitarianism.”

In fact, as I’ve demonstrated elsewhere, the postmodernist (even beginning in Nietzsche) tendency to affirm a purely immanent ontology is actually, in the end, that which negates the possibility of freedom. The Ouroboros is fated to an eternally unsatisfactory meal; nothing new or creative can ultimately arise! Nietzche’s “eternal return,” if taken seriously as a metaphysical speculation, ultimately negates the possibility of any “growth” or “increase of power” in the absolute sense.

Our “metaphysical monism” is, in fact, nothing other than an ontology of pure gift and utter creativity and freedom. Far from our essential participation in the “whole” negating our freedom or even our “absoluteness” as subjects, it guarantees that our very being is always-already, in itself, an ekstasis beyond our nature (consider how we’ve demonstrated this structure in time and its relation to eternity). The primordial disposition of our being is, thusly, one of “wonder” as we take in and are taken into a reality greater than ourselves. And yet, in a sense, it is possible for the whole creation and the whole God to indwell within us, as the saints testify. Our total reciprocation of God’s kenosis occasions our total reception of the gift of creation, which is convertible with our deification in accordance with our logos, which is one in the Logos.

And so, our always-already being “beyond ourselves,” in a sense, guarantees from the outset that any misguided philosophical skepticism is bound to fail. In artificially and unjustifiably elevating self-evident (self-relational, via autonomous reason) certainty as the criteria of truth, modern philosophy has emptied the subject of its phenomenological/personal content because all of this content is given as a gift. Sartre, Zizek, and even the idealists (Kant’s transcendental apperception, Hegel’s Night of the World, etc.) seem to have encountered the purely “empty” subject, which is only the pure negativity of withdrawal if looked at from an ungrateful perspective that implicitly denies the subject’s giftedness. Looking at it from another angle, the subject’s “emptiness” is its infinite potential and its power to take on innumerable predicates. Ultimately, this points towards our final purpose, which is to be fully united with our Creator in a union of “perpetual progress.” For St. Gregory of Nyssa, the eschatological state of creation will be one of unceasing, dynamic ekstasis into the life of the infinite God. Our own infinity can be satisfied, ever self-transcended, through participation in God’s infinity because, as discussed in our post on Eriugena, God is even beyond infinity itself.

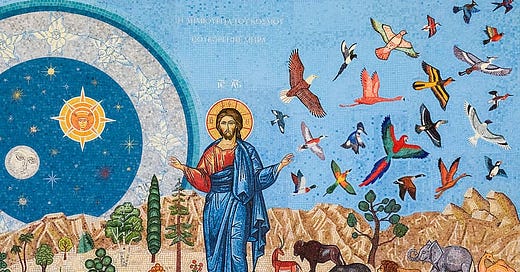

God and creation itself are an overabundance of positivity. God is the kenotic God in Himself as Trinity, and creation is the gratuitous expression of this kenotic life through the inclusion of contingent creatures in the eternal life shared by the Father to the Son in the Spirit. Creation is Incarnation, and here we must stress, against Thomas Aquinas, that the Incarnation of the Word would have occurred regardless of the fall. St. Maximus must say this because if creation truly is incarnational in its foundation, then the total union of creation with its Creator must be in the Word. Nowhere does “negativity” have any place because our being is grasped not first and foremost as other from God but in His light and, properly, as a manifestation of His self-emptying light. The Word becoming flesh is not, ultimately, a response to human sin (as sin has no being, it does not call or respond). Our “dialogical ontology,” therefore, must exclude sin from the outset and locate it with the creature’s failure to reciprocate God’s call. Our otherness is what makes our sin a possibility, but it is equally what secures our essential participation in Him because our particular being can ultimately only be explained in light of His. Our otherness from God is secured in our essential participation in Him, which equally guarantees that our being is, of necessity, “gift all the way down,” as the great John Milbank is fond of saying, and the actualization of our being is precisely equal to the degree of our reception/reciprocation of our own being.

Nietzsche desired to affirm becoming, but because he denied his createdness, he could not imagine a true infinity or a true end! Eternal repetition is, in the end, an entirely imaginary notion that can only be lived in a spirit that refuses to either truly reconcile with or leave the past behind. It is like the epoche Fr. Pavel Florensky described in The Pillar and Ground of the Truth because it’s the contradiction of desiring to be (eternal being, even!) without actually participating in what being is; without recognizing being as participation. Nietzsche’s “power” is—can only be!—a sort of impotent, self-negating expression of self-will over the other. Notice: in order for Nietzsche to think of activity at all, it can only be in the mode of consumption and destruction. He declares that everything is “will to power—and nothing besides!” and describes a self-enclosed world of competing forces. Nietzsche himself seemed quite fond of what was genuinely beautiful, but his spirit was deformed and he projected this in his metaphysics. It’s fascinating that at the height of his “spiritual” contemplation of the eternal recurrence, he dreads never being able to escape his mother and sister. Perhaps Nietzsche’s metaphysics are what caused him to adopt an essentially anti-reconciliatory spirituality, a total inversion of Christianity. He never contemplates forgiving his family, in fact, the eternal recurrence seemingly renders this freedom an impossibility.

But I’ve said enough prefatory remarks, as I simply wanted to set up an anti-Nietzschean/postmodernist context to put forward

’s ontology of peace, which is convertible with St. Gregory of Nyssa’s participatory ontology. “Becoming is an ecstasy, and nothing besides” successfully inverts and redeems Nietzsche’s will to power equivalent:This is the ultimate speculative context in which I want to advance the claim for Gregory of Nyssa's treatment of the infinity of God and of creaturely epektasis: the analogy of being—the actual movement of analogization, of our likeness to God within an always greater unlikeness—is the event of our existence as endless becoming; and this means that becoming is to be thought, for Christians, without resort to the tragic wisdom of any metaphysical epoch ("Platonism's" melancholy distaste for time, change, and distance, despite their necessity, or Hegel's dialectic, or Heidegger's resolve, or any other style of thought that can think becoming only "backwards" from death). Both our being and our essence always exceed the moment of our existence, lying before us as gratuity and futurity, mediated to us only in the splendid eros and terror of our in fieri, because finite existence—far from being the dialectical labor of an original contradiction—is a pure gift, grounded in no original substance, wavering from nothingness into the openness of God's self-outpouring infinity, persisting in a condition of absolute fragility and fortuity, impossible in itself, and so actual beyond itself. Becoming is an ecstasy, and nothing besides; it is indeed a constant tension—between what a thing is and what it is not, between its past and its future, between interior and exterior, and so on—but it is not originally a violent departure from the stability of an original essence.1

David Bentley Hart, The Beauty of the Infinite.

“Creation is Incarnation.” Amen. Amen. Amen.

And like DBH also confirms, man is therefore human and divine by nature. Man cannot become something other than what he is always already by nature (at least in potential).

Salvation is not a result of the Incarnation. Salvation is theosis - the actualization man’s potential as the image of God into likeness with Christ.