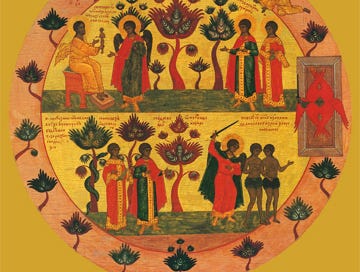

In Genesis 3:14 we are given a rather strange curse placed against the serpent who tempted Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, leading them into sin. We are told that the serpent shall crawl on its belly and eat dust all the days of its life. As this article demonstrates, we know that the serpent in the garden was the devil, and so the curse placed against the serpent can be read along these lines as a more profound statement about the devil rather than simply a curse against snakes in general. While it is true that snakes crawl on their belly, this is pointing towards a more symbolic curse against the spiritual serpent who is the devil. What exactly is this saying about the devil? We know from this article that the curse of eating dust applies to the devils feeding upon the corpses of humanity, the rottenness of sin. Human corpses are the most ritually unclean thing someone could possibly interact with under levitical law, and that is because the levitical categories of clean and unclean are about that which symbolises life and that which symbolises death. Death was introduced to the world as separation from God in Genesis 3, and so anything that symbolises this movement away from God – which can also be categorised as a lack of movement (when you die you stop moving) – is deemed to varying degrees unclean. The serpent is clearly unclean based on just its association with human corpses, but there is another aspect to this uncleanness that we find when we explore the symbolism of its locomotion via belly.

In Levitical law animals are divided into clean and unclean for varying reasons, but a motif that undergirds the categorization of all the types of animals is their method of movement. One of the determining factors of if a land animal is clean is if it has split hooves. Split hooves both separate the animal from the ground which has become cursed (a la Genesis 3:17) and allows the animal to have more precise movement, picking and choosing which areas suitable for life on this cursed ground it should move towards. Similarly, fish are deemed unclean if they lack scales or fins. Scales act as symbolic armour against the cursed ground which the fish swim through, creating a degree of separation between them and the static death of the fallen world. Fins, similar to the split hooves of land animals also allow the fish to move more precisely towards areas suitable for life. Birds are a little trickier, but as explained in this article we know that they are not an exception to this locomotive motif (locomotif, if you will). What does this mean for the serpent who crawls with its bare belly across the face of the earth? It means exactly what we hear in Leviticus 11:41-43, which is that animals which crawl across the ground (whether by belly or with feet) are detestable.

James B. Jordan notes that the word for detestable here is used almost exclusively throughout the bible in relation to ritual idolatry. What is interesting is that in Leviticus, however, it is used almost exclusively in the context of animal and dietary laws. There is a sense in which diet and worship are related, this is why it was such a big deal that Paul specifically says in Romans 14 that buying meat sacrifice to idols is okay. Consider how it is that the serpent tempted Adam and Eve to sin, it was by eating that which they were not prepared to encounter. This is the original “becoming unclean” of humanity. Eating is one of the most basic means by which we interact with – commune with – creation. When we eat we take pieces of the creation, and our bodies metabolise it in order that the material of that piece of creation becomes a part of us. It was in the unjust and untimely interaction with creation through the eating of the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil that Adam and Eve fell. You are what you eat, and if you eat something incompatible with the metabolism of your body, that is a step towards disorder, disintegration and death. It makes sense, then, that the consumption of any creature which symbolically represents this movement towards death is of particular issue in Levitical law. It makes sense then that there is a strict rule against communing with the creature who is the very one who tempted man to sin and curse the ground in the first place by eating. The serpent is cursed with feasting on the dust of dead men, and just as we are joined to Christ by a mutual eating in the eucharist, the “table of demons” (1 Cor. 10:21) is constituted by the mutual eating of mankind and the serpent. It is through this idolatry, the worshipping of that which is not God, that we are joined to the unclean belly of the death-dealing serpent.

The word for belly in Genesis 3 – ‘gachon’ (גָּחוֹן) – is only used twice in the entire bible. Once in Genesis 3 and another time in the levitical condemnation against eating animals who crawl upon their belly. In Jewish tradition, it is said the middle letter of the entire pentateuch – or torah, the first five books of the bible – is the letter ‘Vav’ (ו) in the word ‘gachon’ (גָּחוֹן) in Leviticus 11:42 which is the word for belly. In a sense, the symbolic middle point of the torah (the law) is this word ‘belly’. In Romans 7 we are told that the law existed in order that the sin of man may be increased. The entire purpose of the mosaic law, and the old testament as whole, was that of bringing forth to its fullness and maturing the duality introduced into humanity by the fall of man – the duality of good and evil. The purpose of the old testament was to both mature the good and concentrate it through Israel, into the righteous line of Judah all the way down to the single person of Mary out of whom we get Christ; as well as the bringing forward of evil to such a degree that it could no longer be confused with the good, in order that it may be destroyed by Christ once and for all. Christ accomplishes this by entering into the law and fulfilling it even unto the point of dying, despite His innocence from the fall. Romans 7 tells us that the law was death unto man, precisely because of its revelatory purpose of explicating the fall of man which was present in all things. Christ entered the “belly of the earth,” (Matthew 12:40) and by doing so entered into the consequence of death which permeates the old testament law and destroys death. Christ makes even that which was most unclean, death itself, no longer unclean, but rather a passage towards redemption and glorification through His Life. Even the death-dealing serpent and the symbols associated with him find themselves barren before the all-encompassing work of Christ. Christ joins even the unclean “belly” of the earth to Himself, and by doing so redeems that which was stolen. We can see this symbolism go even further when we see Christ identified with the bronze serpent of Numbers 21 in John 3:14-15. Christ unites all things to Himself and shows how even the unclean belly of the serpent is not irredeemable.